Tuesday, November 19, 2019

Dr. Julie Cwikel presented results from recent social epidemiology research on perinatal maternal mental health care

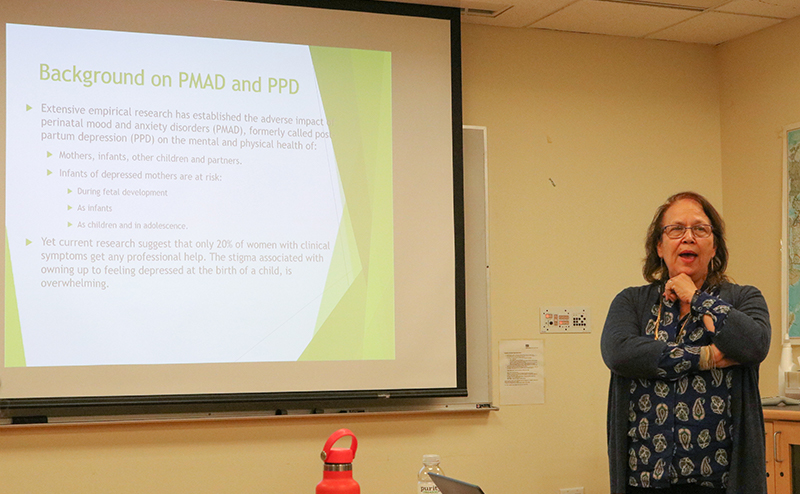

On Tuesday, November 12th, the Boston University community welcomed Dr. Julie Cwikel for a discussion on perinatal maternal mental health challenges and outcomes collected from her recent research on Arab and Israeli women in Israel. The event was co-sponsored by the BU School of Social Work’s Center for Innovation in Social Work & Health, and BU School of Public Health’s Department of Global Health and Maternal & Child Health Center of Excellence.

Dr. Cwikel, who is a chaired full professor in the Spitzer Department of Social Work at Ben Gurion University of the Negev in Israel, first gave a brief overview of social epidemiology. She then discussed the importance of perinatal mental health, which encompasses postpartum depression as well as mood and anxiety disorders as Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders. Dr. Cwikel said that infants of depressed mothers are most at risk: she estimates that, of the 10-20% of new mothers affected by postpartum depression, only 20% obtain the help they need at the time of their symptoms. “These infants,” cautioned Dr. Cwikel, “are getting mothering that will severely limit their human potential.”

Dr. Cwikel first highlighted her 2010 study of pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum experiences on Israeli women in Negev. Researchers expected that maternal anxiety would decrease with each successive birth for mothers—yet, surprisingly, 30% felt a high degree of childbirth fear and anxiety up until delivering their fourth child. Furthermore, postpartum depression and anxiety made women less likely to breastfeed their babies or even have subsequent children—threatening a woman’s ability to have and care for children. Interestingly, however, women who reported a history of fertility problems were less likely to highlight fear and anxiety around their birth experiences, which might be linked to the long journey many have had to finally arrive at childbirth.

Another of Dr. Cwikel’s studies focused on differences in Israeli Arab and Jewish womens’ perceptions of birth experiences in Israel. A higher percentage of Arab women reported feeling afraid during labor, that their births were traumatic, and that they experienced an unsettling degree of medical intervention during their labors. Being out of the cultural majority resulted in a large disparity in how women perceived their birth experiences, and indicated that women who are not from the dominant cultural background might need more support when giving birth away from their home culture.

Dr. Cwikel also mentioned the success of two specific interventions designed to reduce stress and anxiety for new mothers. The first, a Visiting Moms program wherein volunteer mothers visited new mothers in their homes, was successful in reducing symptoms felt by mothers with mild to moderate postpartum depression. The second was a program called CBArt which combined cognitive behavioral therapy principles in art-based interventions. The mothers who participated in both individual and group-based CBArt sessions responded positively, with reduced postpartum depression and anxiety symptoms.

A fifth cross-sectional study spearheaded by Dr. Cwikel identified preferences and barriers to postpartum treatment in Israeli women in their first six months after giving birth. Though 70-80% of new moms report feeling postpartum “blues,” Dr. Cwikel noted that many women feel shame and stigma about it and are not forthright on clinical postpartum depression surveys. “They don’t want to be told they’re bad mothers,” or feel prodded into treatment, she said. The forthcoming study yielded important information about mental health stigma and how new mothers prefer to access mental health services: women without a postpartum depression diagnosis preferred community-based mental health treatment outside of a psychiatric framework, whereas women with postpartum depression indicated greater comfort with seeking psychiatric-based mental health care in the months after childbirth.

Dr. Cwikel’s research emphasizes the need for culturally-sensitive mental health interventions that can help new mothers get the support they need, when and how they need it. Through her lobbying efforts and activism in Israel, she has also used these social epidemiology findings to support law and policy changes to improve the type and delivery of maternal mental health resources.

References

- Segal-Engelchin, D. Sarid, O. & Cwikel, J. (2010). Pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum experiences of Israeli Women in the Negev. Journal of Prenatal and Perinatal Psychology and Health. 24(1):3-25.

- Halperin, O. Sarid, O. & Cwikel, J. (2014). A comparison of Israeli Jewish and Arab women’s birth perceptions. Midwifery 30(7):853-861.

- Czamanski-Cohen, J., Sarid, O., Huss, E., Ifergane, A., Niego, L. and Cwikel, J. (2014). CB-ART- The use of a hybrid cognitive behavioral and art based protocol for treating pain and symptoms accompanying coping with chronic illness. Art and Psychotherapy. 41(4):320-328.

- Cwikel, J. Segal-Engelchin, D. & Niego, L. (2017). Addressing the needs of new mothers in a multi-cultural setting: An evaluation of home visiting for new mothers – Mom to Mom (Negev). Psychology, Health and Medicine.23(5), 517-524.

Article by Mariah LeStage, photo by Nilagia McCoy.