Tuesday, June 05, 2018

At 8:30 on a beautiful Saturday morning in April, students from the Boston University (BU) schools of social work, public health, medicine, dentistry, and Sargent college as well as health practitioners across a wide range of disciplines trooped into the Hiebert Lounge on the 14th floor of the BU Medical classroom building. They were devoting this precious time right before finals to explore how they as current or future health practitioners could deepen their understanding of intersectionality and health to provide better care and eliminate health inequities for people with multiple marginalized and intersecting identities.

The student-led conference was the brainchild of Jackson Rodriguez, who had experienced multiple frustrating encounters in their attempt to access health care that met their needs. These experiences led them to become a student at BU School of Social Work and inspired the vision for the conference.

“My hope in co-organizing [the conference] is to provide intentional space where we center the lives and stories of the people we will encounter not just in the doctor’s office or therapist’s room, but … the people we interact with anywhere on a daily basis,” explained Jackson. “I believe that by opening up ourselves to fully listen and engage with people who are consistently absent in mainstream media, we can move toward seeing and talking about these barriers in an effort to break them down over time.”

Planning committee co-leaders (from left) Students of Boston University School of Social Work (BUSSW) Megan Niegisch, Rebecca Bilodeau, and Jackson Rodriguez: and staff of BUSSW Center for Innovation in Social Work & Health Nandini Choudhury, Research Assistant, and Madi Wachman, Program Manager

Rebecca Bilodeau and Megan Niegisch, students at BU School of Social Work (BUSSW) explained that the term “intersectionality”, was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989. It is about how, at a system level, people are pushed to the margins, and their oppression is compounded based on overlapping, interconnected aspects of their identities.

To explain what this somewhat abstract-sounding concept means in the lives of real people, three speakers related the challenges, discrimination, and injustices they experienced when the US health care system failed to support their multiple layers of identity and cultural beliefs.

When the health care system collides with multiple layers of identify

Keynote speaker Mickey Thomas: “Trying to access mental health services was one of the most frustrating experiences ever.”

Keynote speaker Mickey Thomas works as an after-school elementary school teacher and facilitates workshops on topics from addressing ableism in LGBTQ spaces to sexual education that is accessible to all. The common face of depression – that of a white, middle-aged, upper middle class cisgender woman – did not resonate with their experiences as a Black teenager. “If you’re black, you don’t have the right to be mentally ill,” they explained. “I was taught I had to be strong. We are always taught to suck it up. It is not cool that you are taught that you have to suffer in silence because you don’t deserve access to care.”

Sandy Ho shared her experiences in the form of a letter to her first social work therapist.

Sandy Ho is a disability community-organizer and the founder of the Disability & Intersectionality Summit. In an open letter to a social work therapist, she explained how the treatment she received made her feel dismissed and ignored. “I was not sure I was allowed to give voice to my pain,” she said. “I did not have the privilege to be listened to.” Sandy explained to her therapist the importance of being viewed as an autonomous individual, not as a recipient of services. She ended with a challenge to all of us listening to her letter: “How will you acknowledge the wholeness of the next person who comes into your office?”

Nikki Friedman: Having a sense of self does help, but it doesn’t make it [the struggle with mental health] go away. It is still going to be a struggle and I am not afraid to be open about it.”

Nikki Friedman, a student at BUSSW with a focus in macro practice, draws on her lived experience with mental illness in her work as a peer specialist with Riverside Community Care. Nikki shared her own experiences seeking mental healthcare, and highlighted the limits of employment support for people struggling with mental illness. Nikki recognized her privilege in living in a white, upper middle class family as enabling her to receive plenty of care, and cited the desire to ensure that all people have access to care as a motivation for pursuing social work.

Breakout Sessions

A series of breakout sessions gave attendees the opportunity to hear from organizations that work with communities who often are marginalized by the dominant culture, leading to challenges gaining access to culturally appropriate, respectful services.

Boston GLASS presented a provider-focused discussion of challenges in accessing health care among LGBTQ+ populations.

Shannon Al-Wakeel, executive director and co-founder of the Muslim Justice League, talked about how “counter-extremism programs” impact marginalized communities.

Organizations share information with attendees

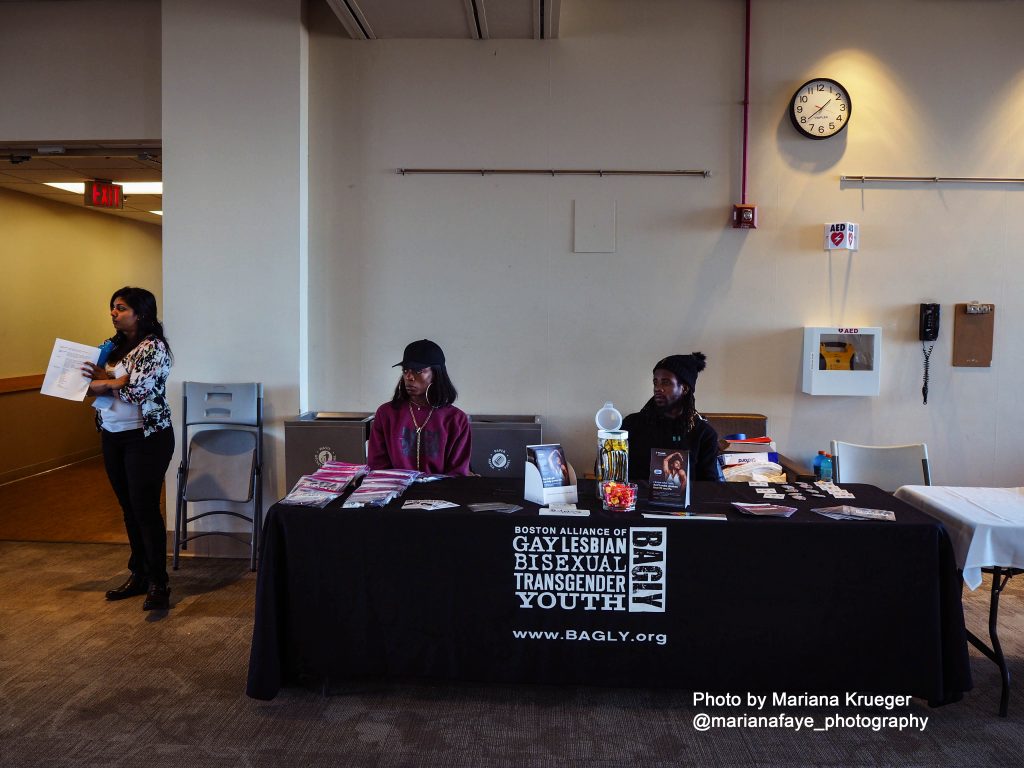

Participants also had the opportunity to explore materials and interact with representatives from several organizations at tables set up around the room. Presenting their services and resources were ZenCare, BAGLY – the Boston Alliance for Gay and Lesbian Youth, Boston GLASS, the Triangle Program at Arbour-HRI Hospital, and the Bisexual Resource Center.

Two attendees talk with a representative from the Triangle Program at Arbour-HRI Hospital

The Boston Alliance of Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Queer Youth was on hand to share resources and information about their services with attendees.

Afternoon panel shares experiences working with people with marginalized intersecting identities

Dawn Belkin-Martinez, clinical associate professor, BUSSW, moderated a panel of professionals who serve marginalized communities. The panel shared their perspectives on breaking down barriers to quality care for people with multiple, marginalized and intersecting identities.

The panel included Paula Cushner, a nurse practitioner who works with adults experiencing homelessness at Cambridge/Somerville Healthcare for the Homeless Program of the Cambridge Health Alliance, Tfawa Haynes, a clinical social worker and research study therapist and clinical supervisor at the Fenway Community Health Center, the Fenway Insistute, and AIDS Action Committee of Massachusetts, Tanekwah Hinds, the women’s health program coordinator at Fenway Community Health Center, and Dave Rini, the Prison Rape Elimination Act project coordinator at the Boston Area Rape Crisis Center. Panelists reflected on the role of their personal and professional identities in how they serve clients, how they strive to welcome all people, and how they learn from their clients.

Panelists front row from left: Paula Cushner, Nurse Practitioner, Cambridge/Somerville Healthcare for the Homeless Program of the Cambridge Health Alliance; Dawn Belkin-Martinez, Clinical Associate Professor, BUSSW (moderator); Tanekwah Hinds, Women’s Health Program Coordinator, Fenway Health

Second row from left: Dave Rini, Prison Rape Elimination Act Coordinator, Boston Area Rape Crisis Center; Tfawa Haynes, Clinical Supervisor, Fenway Health.

Several themes emerged during the course of the panel discussion. The clinics where Paula works enable patients to have direct access to and build relationships with service providers. “If they need more than what we can offer, then we will do everything we can to get what they need. We have a motto: If we tell you we’re gonna do it, we’re gonna do it.” Dave shared that he has to do a lot of “code switching.” “When I speak with staff in the correctional system, I need to ‘talk lawyer’ to them in a way that is effective and informed but not threatening,” he said. But with clients, he puts the lawyer talk aside and tries to speak in a way that helps clients regain the sense of agency that was stripped away by sexual violence. These experiences reflect the importance of building relationships and trust with clients by meeting them where they are/adapting to different situations.

The role of a professional or practitioner’s identity also plays a role in service delivery, Dave emphasized that his experiences are different from the incarcerated individuals he meets with, particularly in the sense that he has never been incarcerated. “I have come to understand that I don’t necessarily know what folks are going through. So I try to ask a lot of questions—questions that don’t have assumptions in them.” Tfawa highlighted bringing a sense of personal authenticity to the work. “When someone comes into a session with me, there’s often times this blank slate where they can project onto me,” explained Tfawa. “But I am in no way blank…You can’t know everything about the other, but you can know about yourself. I try to bring the truth about who I am and not hide that from them.

The panelists also highlighted the need to engage clients in healing and center the experiences and strengths of community members. “I put the expertise back on the client, move the desk away and work side by side. We are here working on this together,” said Tfawa. Providers may sometimes perpetuate oppression by putting people into binary boxes instead of allowing them to use their own language to define themselves, said Tanekwah. In her role as community organizer and activist, Tanekwah recognizes the people who are already doing the work and seeks to uplift their voices. “I use the outreach I have to uplift those voices and communities by empowering them to do a workshop, for example.”

In closing

Lydia X.Z. Brown, Disability Justice Organizer and Advocate wraps up the conference.

Lydia X.Z. Brown, a disability justice advocate, organizer, and writer, summarized the day’s discussions by explaining the distinction between disability rights and disability justice: while disability rights focuses on changing laws, regulations, policies, and programs, disability justice incorporates these efforts into a framework that seeks to transform the intersecting systems in society and culture that lead to patterns of abusive behavior.

“We can’t do the work without asking ourselves who’s not here and why?” Lydia said. Disability Justice asks “how we can build whole communities and value systems that challenge the current ones that devalue some of our bodies and minds?” they asked. “How can we support one another, because we all are worthy, valuable, and desirable, and we all deserve love and care. This is what disability justice has to offer us.”

Lydia called upon participants to be activists, while also showing compassion for themselves, a key message for participants to carry forward into their practice.

Many thanks to our sponsors for making this day possible!

-

- BUSSW Center for Innovation in Social Work and Health

- BUSPH Activist Lab & Santander

- BU-ALPS (Advancing Leadership in Public Health Social Work) HRSA Grant

- BUSSW Office of the Dean

- BUSSW Macro Department

- BUSSW Student Organization

- BUSPH Office of Student Services

- BUSPH Center of Excellence in Maternal and Child Health

#BreakthesilosBreakthebarriers

More photos available on our Facebook album: Intersectionality and Health