What does it mean to be a public health social worker? CISWH’s Boston University Advancing Leadership in Public Health Social Work (BU-ALPS) project explores the career paths and impact of MSW/MPH alumni.

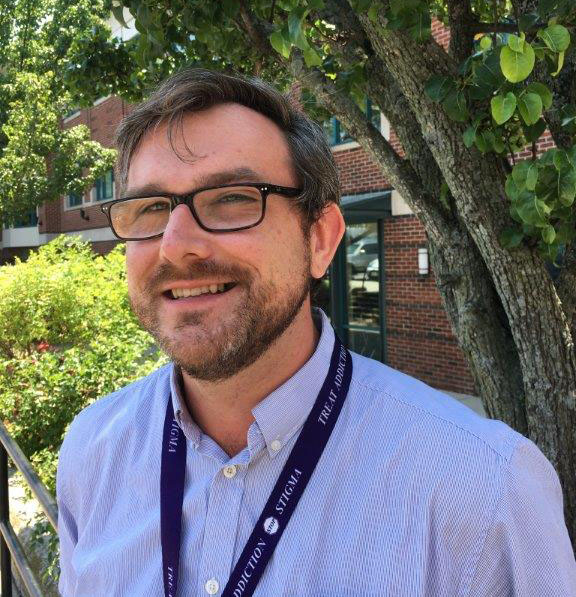

Dan Hogan, MSW, MPH, Substance User Health Program Manager, Codman Square Health Center, Boston, MA

Dan is the Substance User Health Program Manager for Codman Square Health Center in Boston. He graduated from the Boston University MSW/MPH program in 2012/2014 and majored in Clinical Practice at the School of Social Work and Health Policy/Management at the School of Public Health. Even before graduate school, Dan knew he wanted the skills that an MSW/MPH program could provide: “I knew I wanted the ‘boots on the ground’ skills that clinical social work provided, while also obtaining a broader public health lens. Through integrating public health and social work, I hoped to inform my practice and to explore systems-oriented solutions that could respond to the needs of clinical social workers who provide substance user services.”

Dan is the Substance User Health Program Manager for Codman Square Health Center in Boston. He graduated from the Boston University MSW/MPH program in 2012/2014 and majored in Clinical Practice at the School of Social Work and Health Policy/Management at the School of Public Health. Even before graduate school, Dan knew he wanted the skills that an MSW/MPH program could provide: “I knew I wanted the ‘boots on the ground’ skills that clinical social work provided, while also obtaining a broader public health lens. Through integrating public health and social work, I hoped to inform my practice and to explore systems-oriented solutions that could respond to the needs of clinical social workers who provide substance user services.”

Dan sees his current role as a “true blend” of clinical social work and public health. He endeavors to “use the two disciplines to advocate for humane and sensible polices around substance user health, as well as to engage in harm reduction, community engagement, education, prevention and ultimately to help reform current substance use methodologies.” Dan points out that “both lenses are crucial in developing the skill sets need to approach these challenges. Substance user health does not improve based on a clinical visit alone,” because while individuals do need treatment, they also need opportunities and systems-level services that that can impact substance use. “I believe that all public health and social work professionals are best equipped to deal with the suffering in our society when they’re able to view social ills through both individual and systems lenses. By treating the individual, we can help one person in a profound and meaningful way. But integrating that help into a broader, public health and public-facing approach, we can support the revitalization of communities that have been devastated by addiction and other health inequities.”

“I believe that all public health and social work professionals are best equipped to deal with the suffering in our society when they’re able to view social ills through both individual and systems lenses.”

Dan notes that MSW/MPH trained social workers have the ability to step outside a narrow professional viewpoint and see this greater mission. He also feels well-equipped “to wear multiple hats” while working in health care, and yet he admits to occasional challenges: “There are moments when members of one profession are unable to see things the same way you do as a public health social work professional. For example, a clinical social worker may feel that their priority is to the individual client and that everything else is secondary. The public health practitioner may view that intervention as one of many, and may fail to understand the power of many individual interventions at the population health level. The MSW/MPH professional must make difficult decisions at times, choosing between values that may not always be aligned such as population versus individual orientation. A truly enlightened public health social work professional must balance these difficult choices and attempt to address both. At times, this burden may tax or vex the MSW/MPH professional, but it’s our obligation to stay the course and see initiatives through.”

Dan’s advice to MSW/MPH students: Start with a small focus and build yourself up from there. “Often, we don’t know the true nature of the work we think we want to do until we actually experience it ourselves. My original career goals share many elements of my current one, however, the details have changed. Time, place, and my own experiences have resulted in an ever-evolving view of health systems, and the realization that change occurs through gentle, yet sustained advocacy.”

This profile is excerpted from Advancing Leadership in Public Health Social Work Education: MSW/MPH Program Handbook. This free resource, designed to help schools with their efforts to establish, promote, improve, and evaluate MSW/MPH programs, was produced by CISWH’s BU-ALPS project and funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. This information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government.